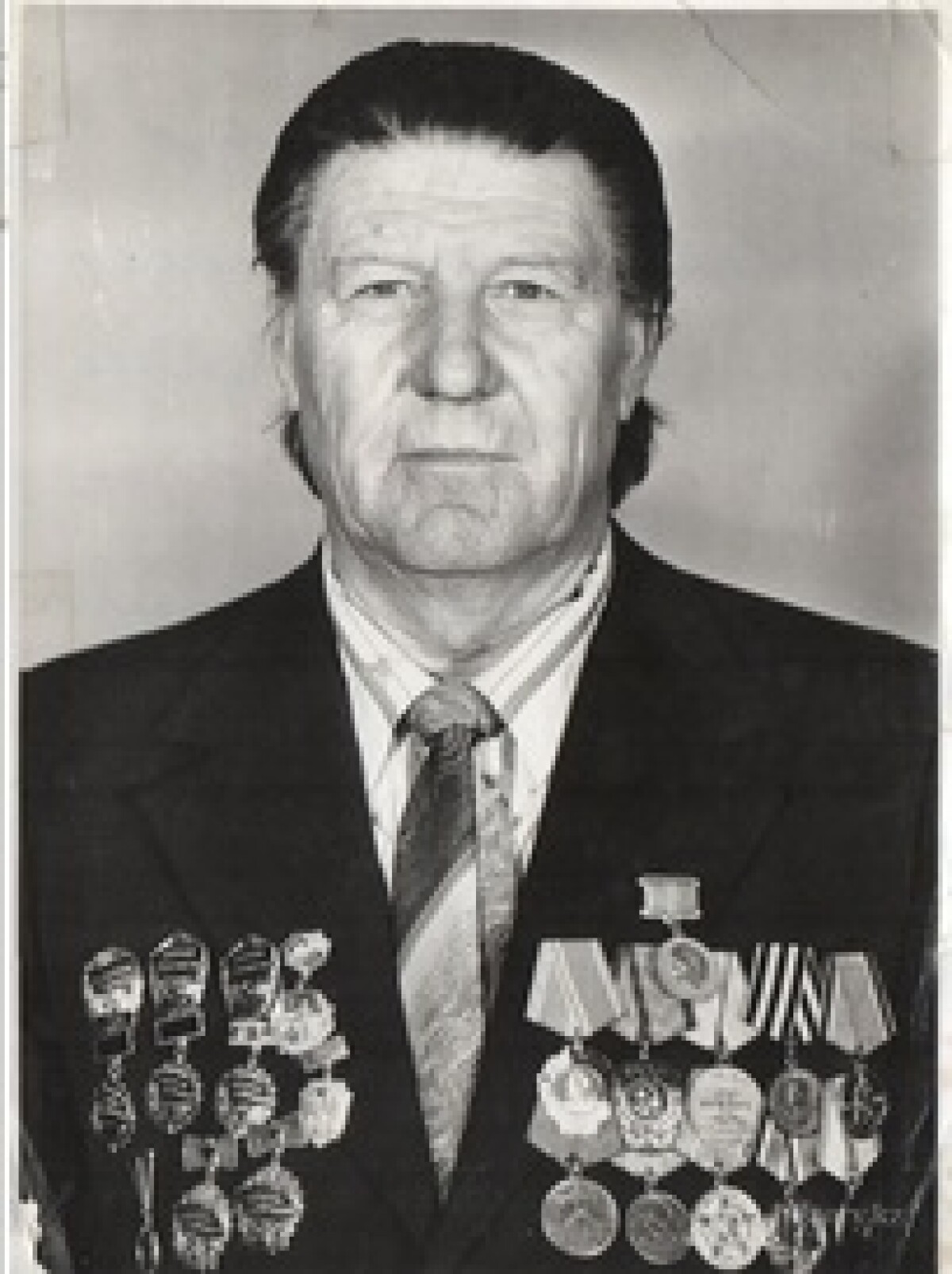

My great-grandfather Nikolay Skovorodko was born in 1924 in the village of Balabanovo. His father fought on the fronts of the World War I. My great-grandfather grew honest and hardworking boy, but like other children he was a fidget. Once he took his mother’s headscarf and used it like a parachute jumping from a roof. He loved playing accordion and was always soul of the party.

He reached the age of 18 and in August 1942 he was integrated into the Red Army. But he didn’t go to the front. He was among those literate young men who were sent to the Leningrad Military Liaison School which was located in the city of Uralsk at that time. And he studied structure of portable radio transmitter and decoding radiograms — everything that future telegraphist should know.

Though the duration of the course was one year ever three months a group of cadets went to the front from the building of the Uralsk Pedagogical Institute. They were so called "cadets who have received accelerated training". Several months later came the turn of Sergeant Skovorodko. Together with comrade he went to Moscow by military echelon. But the war again left him for a while. Nine more trained cadets of forty were sent to the front while strong and tall men, including Skovorodko were assigned to military camps near Ivanovo. "So I was integrated into the landing forces" — my great-grandfather told. He had to train again. The most difficult was to adapt to the height and parachute descents. They were taught how to jump with parachute, shoot precisely, run long distances and fight hand-to-hand. Of course, being radio operators they were trained how to acquire radio signals in all conditions.

He started fighting only in 1945. But the battles were the most serious as the enemy fought vigorously. My great-grandfather remembered the battle between Lakes Velence and Balaton most of all. At first, the Soviet Army had a defensive military position and fought against panzer divisions of the SS. Day after day radio operators Skovorodko and his friend Yaryev acquired and sent radio signals.

My great-grandfather met the Day of Victory (9 May 1945) near Prague. He was on duty and listened to news from Moscow. Moscow reported on the German capitulation. Having thrown his headphones Nikolay Skovorodko raised clenched fists. He looked back and see his Platoon Commander Savelyev:

— What’s wrong, Skovorodko?

— It’s Victory, Comrade Lieutenant, Victory!

For most soldiers the war finished on 9 May 1945. But Sergeant Skovorodko and his comrades continued to fight against Nazi units in Czechoslovakia. He returned home in 1947. He was the third of those twelve recruited from his area to come back.

After the war my great-grandfather worked much. He cultivated thousands of centners of grain.

Military awards were complemented by labour awards. For hardworking he was awarded the highest orders of the Soviet Union — the Order of Lenin and the Order of Red Banner.

He always was responsible for his work. He loved to produce everything with his own hands, including spades, rakes, wheelbarrows, and so on. He read many books and additional literature. My great-grandfather had a garden and he used to give the harvest to the local school, kindergarten or neighbours free of charge.

Nikolay Skovorodko had five children, including Nikolay, Vladimir, Aleksandr, Olga and Natalya, eight grandchildren and twelve great-grandchildren.

He was respected by the family members and colleagues. He had a long and happy life. But the most important thing is he believed in prosperity of our country.

Petrushkevich Danil,

grade 10 student of the Makarovo Secondary School,

the village of Makarovo, West Kazakhstan region