Throughout much of the nineteenth century, population estimates for the Sioux and the Kazakhs varied considerably and were largely based on lodge or yurt counts by visitors and some government officials. For example, according to Stephen Riggs, by the 1850s, the Dakotas numbered about 25,000. Riggs did not include the Lakota in his estimate. A later approximation based on some government information not available at midcentury that included the so-called western Dakota suggested that the population was closer to 40,000. In the 1830s, Aleksei Levshin published one of the first demographic estimates about the Kazakhs. Levshin believed there were roughly 190,000 yurts in the Little Horde, 500,000 in the Middle Horde, and 100,000 in the Great Horde.

Using a figure of six people per yurt, he concluded that there were almost 4.7 million Kazakhs. This method to approximate population was similar to the lodge counting conducted by Americans to estimate the total number of Sioux. By the latter part of the nineteenth century, official American government statistics shed only partial light on the Sioux population. By the 1870s, some Sioux lived on reservations; other Sioux refused to settle there. In the 1870 Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, the Dakota Superintendency census calculated the total population at 27,921, but it likely included various Sioux bands and non-Sioux, such as Cheyenne or Ponca. By 1880, having finally forced all Sioux to live on various reservations, the report calculated that the Sioux population was 31,547. That number declined during the early reservation years—between 1880 and 1910—perhaps due to infant mortality or Sioux leaving the reservations following the 1887 Dawes Act. By 1910 the Sioux numbered only 27,588. The Russians, however, only conducted their first official census in 1897, and it concluded that there were 4.5 million Kazakhs in all territories of the empire, with an average of four people per yurt. According to the census, 3.4 million lived in the four steppe districts, and the others lived in Turkestan and Siberia. These midcentury estimates, and subsequent official American and Russian census data, demonstrate one of the major differences in this comparison: the number of Kazakhs far exceeded the number of Sioux.

Unquestionably, American Indian populations decreased significantly during American expansion and internal colonization and suffered immeasurable losses due to disease and military confrontations. This decline among American Indians, and to some extent the Sioux, fostered expectations by many contemporary observers, missionaries, government officials, and soldiers that the American Indian was on the verge of extinction. The American people readily accepted American Indian decline as the inevitable contraction of an ostensibly backward, uncivilized people confronted by civilization. The Kazakhs, on the other hand, did not endure similar population declines in the nineteenth century. Levshin’s estimate appeared generally accurate based on Russian 1897 census data.

Although difficult to conclude with certainty, the demographics might also explain the extended period Russia required to conquer and subsequently colonize the Kazakh Steppe. From 1732, when some Kazakh khans first swore allegiance to the Russians, it took another 115 years for Russia to quell that last major Kazakh martial resistance to Russian colonization. In the United States, conquest occurred from roughly 1851 to 1890. Nonetheless, the Sioux represented the dominant force in the northern plains before 1850 and one of the largest demographically that the Americans encountered. The Kazakhs, as well, constituted a large population situated on the Russian frontier and represented a significant barrier to Russian expansion.

After the Second World War, however, Lemkin’s term—genocide—gradually provided scholars a new interpretative framework in which to examine American internal colonization and Native American population decline. Since the 1960s, many American scholars have suggested that the American government and people committed genocide against the indigenous population. Some even argued that this genocide started when the first Europeans landed in the Americas. Various American scholars equated expansion westward and the expulsion of natives as cultural genocide; others observed clear cases of physical genocide against, for example, California’s natives, certainly in the years following the 1848 California gold rush. By the 1970s, Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee thoroughly popularized the concept of genocide against American Indians, and it remains a topic of heated debate among scholars, journalists, and activists. Other scholars—most notably, historian Gary Clayton Anderson—argued that it was not genocide but “ethnic cleansing.”

In the Kazakh case, Soviet scholars, both Russian and Kazakh, did not typically apply the term genocide to reinterpret Russian internal colonization. Serious discussion, however, chiefly emerged during Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost reforms of the 1980s and captured many Kazakh nationalists’ imaginations in the years immediately following the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991. Since then, Kazakh and foreign scholars generally identified two distinct instances of possible genocide: the 1916 central Asia revolt and the Soviet collectivization famine in Kazakhstan in the 1930s and the subsequent Stalinist purges. The number of Kazakhs who died during these two tragic episodes remains uncertain, and Soviet-era interpretations further shrouded historical examination. The first work to ignite the debate was a 1989 article published in the Soviet journal Voprosy istorii, coauthored by two leading Kazakh historians, Zhulduzbek B. Abylkhozhin and Manash Kozybaev, and highly regarded Kazakh demographer Makash Tatimov. The article, “Kazakhstanskaia tragediia,” spawned numerous scholarly articles and books in Kazakhstan that generated intense discussion in the press and popular media. Most frequently, scholars identify the Soviet collectivization and Stalinist purges among the Kazakhs, in which an estimated 25 to 30 percent of the Kazakh population died, as a clear evidence of state-sanctioned genocide. Most Kazakh scholars believe that between 1.3 and 1.5 million Kazakhs died during the famine, which they frequently describe as genocide; but many western scholars disagree. Historian Sarah Isabel Cameron’s meticulous research led her to conclude, “there is no evidence to indicate that these plans for violent modernization [collectivization] ever became transformed into a desire to eliminate Kazakhs as a group.”

Neither Anderson nor Cameron ignore the violence or atrocities committed against the Sioux or the Kazakhs, but, as Anderson concluded, “many Indian tribes (indeed the vast majority) survived, along with their culture ... This weakens and perhaps makes impossible the argument for calling what happened in North American genocide of any sort.” In the nineteenth century, Anderson claimed, “Genocide did not occur in America, primarily because moral restraints prevented it.” He argued, “For either genocide or ethnic cleansing to occur, a legitimate government must plan, organize, and implement the crime . . . But other actions such as removal or diminishment of ancestral lands require a different description because they are not genocide.” As with Anderson’s argument, the Russian government exhibited no intent to exterminate the Kazakh nation during either the 1916 central Asian revolt or Soviet collectivization. It was not the goal of the Russian government in 1916 or the 1930s to pursue ethnic cleansing either but to suppress a rebellion brought on by war and internal colonization in the former and forcefully implement Soviet modernization policies during the latter.

Tiyospaye and Aul

The Sioux called their small nomadic communities tiyospaye, consisting of several camps (called wicotipi, or households), which joined together and were often based on actual and fictive consanguinity. During the winter months, the tiyospaye camped together; during much of the year, these camps separated for hunts but often reunited for ceremonies such as the Sun Dance. Camps generally consisted of kin but were not solely restricted to direct blood or marriage. Other kin relations included ritual adoption. Outsiders—and this typically included fur traders or members of other tribes—could acquire fictive kinship. Fur traders developed reciprocity networks, which, according to Mary K. Whelan, was an exchange “between socially defined partners” that “symbolized family relations” among the Seven Council Fires. These social or even economic kinship relations were as legitimate as blood or marriage. In 1698 Father Louis Hennepin witnessed one such ritual adoption. The tribe also adopted Hennepin. He explained that after an exchange of “presents,” they “adopt those” and “publicly declare them Citizens, or Children of their country; and according to their Age . . . the Savages call the adopted Persons, Sons, Brothers, Cousins, according to the degree of Relations: And they cherish them whom they have adopted, as much as if they were their own natural Brothers or Children.”

Kinship was an essential factor in Sioux internal relationships at all levels. The codes of conduct and behavior were firmly established, which is not to suggest violations did not occur. For example, the avoidance taboo forbade a married man to look at his mother-in-law, and a similar rule existed between a father-in-law and his son’s wife. This structure created a means by which the change of camp or tiyospaye by an individual or family did not require a fundamental change in behavior. Each individual, young or old, understood and complied with this system, which preserved the essential “harmonious operation” of a tiyospaye. According to Ella Deloria, “kinship had everyone in a fast net of interpersonal responsibility ... Only those who kept the rules consistently . . . thus honoring their fellows, were good Dakotas—meaning good citizens in society, meaning persons of integrity and reliability.” It was, she wrote, “what men lived by.”

Among the Kazakhs, the smallest nomadic unit—the aul—consisted of relatives, usually a father and sons. The next level of kinship was the ru, or taipa, usually translated as “clan” or sometimes “tribe.” Members of the clan might be related, but not necessarily. Clans conjoined into a single zhuz, or horde. As the smallest economic and social unit in Kazakh society, the aul traditionally provided the strongest connection to genealogy and was the most tangible source of wealth and security, but it could also include unrelated members. Auls generally operated as semi-independent units, gathering only for special occasions and wintering together. The economic viability hinged on self-sufficient activities, and the political structures reflected that same degree of independence.

One yurt generally consisted of the nuclear family—parents and unmarried children. When a son married, he remained in the paternal aul, and the family provided him with a share of the familial property—chiefly a yurt—and some livestock. The woman’s family also provided property, household goods, and some livestock as part of a dowry. Rarely did a bride remain in her natal aul. The youngest son, if there was one, usually remained in his parents’ yurt after marriage, in order to care for his parents in old age. When they died, he inherited his parents’ remaining property, including the livestock. Both the Sioux and the Kazakhs practiced forms of exogamic marriage.

Sioux rules of exogamy required a degree of separation between potential marriage partners, discouraging marriage between a couple that shared a common grandparent. In general, it was best to marry outside the kinship group, tracing the lineage as far back as possible to ensure the appropriate separation. Arranged marriage was the norm; however, the young couple might have a say in the matter. Sioux practice also included a bride price, the hakatakus, which the woman’s male relatives received. According to Royal B. Hassrick, the higher social status, the higher the price, usually paid in horses after the Sioux acquired them in the late eighteenth century. The couple had the choice to live in the man’s camp with his relatives or in the woman’s camp alongside her relations. Polygamy was also an accepted practice in Sioux society, but it required a degree of wealth in order to support all of a man’s wives. Levirate occurred as well, but it was not obligatory nor, it seems, frequently applied. A nuclear family shared a tipi, but it was the woman’s property. If a man had multiple wives, each woman should occupy her own tipi.

Kazakh rules of exogamy dictated that marriage could only occur between unrelated partners, traditionally by seven generations of separation. Marriage was a contractual agreement between parents, kalym (bride price) being paid to the girl’s parents. The Kazakhs practiced polygamy, but, generally, only the wealthy had up to four wives; thepractice was somewhat unusual. Kazakhs also practiced levirate. A woman with no sons passed to the younger brother, but she was exempt if she had a son and inherited the property until the son or sons reached maturity. Krader noted, perhaps with a little levity, that levirate was “not loved” by women because if they were compelled to marry a brother who already had one or more wives, the recently widowed woman immediately assumed a subordinate position to the others. She was, simply, no longer the doyenne of her own family. Women were important social and economic partners with their husbands in both Sioux and Kazakh society.

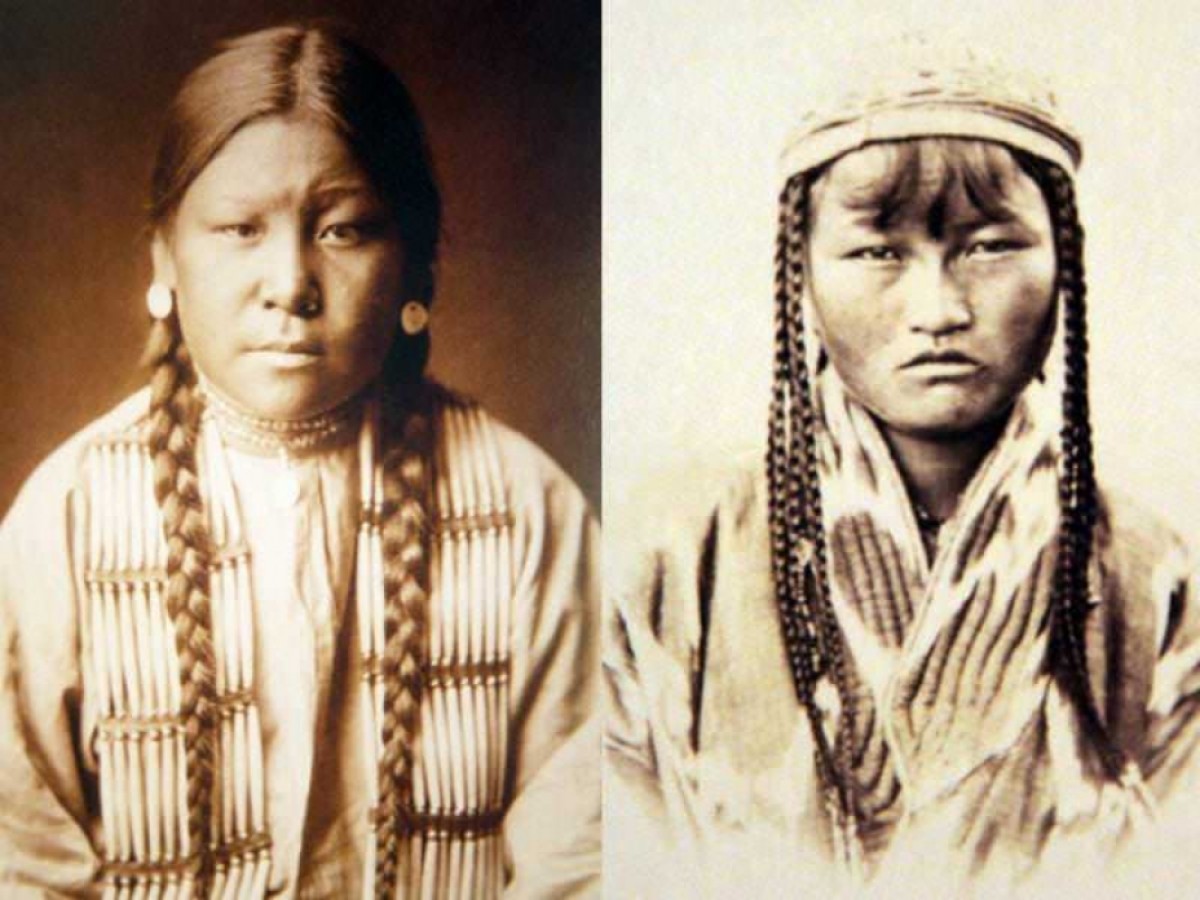

Perceptions by outsiders in the nineteenth century typically characterized women as subordinate in Sioux and Kazakh society. For outside observers, gender roles were an important demarcation between American and Russian women, in comparison to Sioux and Kazakh women—a clear contrast between the relative freedom American and Russian women enjoyed and the “drudgery, subservience, and patriarchal oppression” exhibited in Sioux and Kazakh societies. These ideas reinforced one of the traits that colonizers detected in nomadic societies: that a society’s treatment of its women revealed the level of its civilization. As Sherry L. Smith commented, Americans, undoubtedly a civilized people, “pampered women; savage people enslaved them.” Visitors to a Kazakh aul described the women as “active and energetic, and [they] perform nearly all the labor which should devolve jointly” to men and women; but the men are “distinguished for their indolence.” Another noted that the women cook and do most of the work, while the men are “too lazy to do more than look after the horses,” and “lead a lazy, shiftless life.”

Among the Sioux, women served an essential role in tiyospaye functions. Childbearing, food preparation, and handicrafts were all critically important. Women made the tipis, an arduous undertaking. Women typically put up and took down the tipi, which varied in size. A larger tipi often reflected the husband’s ability to hunt to obtain skins. The expression “[t]he men with the fastest horses lived in the biggest tipis” revealed a husband’s ability to provide for his family. But, Whelan noted, the Sioux “women’s ownership of ‘family’ tipis and the onerous nature of many of their tasks puzzled Euro-Americans because it challenged their Western gender system.” Later, missionaries among the Sioux on the reservations nonetheless considered the status of women to be one of servitude, and only “[t]ime alone can change this prejudice and raise Sioux women from their low condition to that of high and noble position such as is attained and held by women of civilized nations.”

What outside observers either neglected or failed to acknowledge was that Sioux women could speak at camp councils. A Sioux woman could divorce, and she owned the major property, including furs, clothing, the cooking utensil, and other domestic implements. According to Walker, in family matters, a mother’s authority exceeded that of the father. And, like male societies (warrior, dance, etc.), women had societies as well.

Women in Kazakh society also played a critical role. They were never veiled or secluded. Ellsworth Huntington visited some Kazakh camps, and he remarked that women were “continually engaged in their household tasks. They converse freely with men, and make no attempt to keep themselves hidden.” This is something Huntington likely expected to see because Kazakhs were Muslims, and Muslim women, in his understanding of Islamic society, were secluded and veiled. Contrary to expectations, Kazakh women participated in councils and assemblies; they joined in songs and games and “respond readily to jests interchanged with men.”

Sioux and Kazakh women raised the children, engaged in domestic handicrafts, did the cooking and cleaning, and were fully involved in the day-to-day activities of the camp. Men guarded the herds, defended the camp, and made the political decisions; women did everything else. Despite American and Russian perceptions, Sioux and Kazakh women were not enslaved. Observations by Americans, Russians, or foreigners, however, rarely dismantled the power of nineteenth century negative conceptions and perceptions about the Sioux and the Kazakhs, which more frequently, and typically, reinforced false beliefs.