The world of rugs is exciting because there is always something new to be learned or different kinds of rugs to be discovered. There are weavings which have been overlooked, have never entered commerce, and suddenly appear in the marketplace. The rugs presented here represent just such a phenomenon.

In 1966 oriental rug scholar George W. O'Bannon began buying rugs in the bazaars in Afghanistan. In 1974, he found and purchased his first rug of a type shown here. The rug he purchased was sold him as a Kyrgyz rug. The same year he purchased a donkey bag which he assumed to be Beshire Turkoman. A few more of these weavings were purchased in 1975, and since 1976 increasing numbers of them have begun to appear. In general, by 1974 he had seen over 500 pieces of these weavings. Later on, O’Bannon performed research results of which Qazaqstan Tarihy portal quotes in present article.

The rugs are given a variety of names by the Kabul rug merchants including Kyrgyz, Uzbek, Kazakh, Arab, Tatar, and Aimaq. From this different and diverse group of rugs several distinct types were becoming obvious. In the absence of any substantial published information on these weavings in mid-1970s, it seemed that a monograph was warranted which defines two distinct sets of weavings from this broad group. O'Bannon hoped that his tentative classifications will stimulate discussion, further the sharing of present information, and encourage primary field research on these rugs.

These rugs have not been studied, published or researched before 1970s for a variety of reasons. In most rug producing countries the local society and culture determined and influenced the types of rugs available in the marketplace. The result was that each area undoubtedly has rugs or weavings which did not enter commerce because the local population and merchants did not like them or looked down on them as inferior to other weavings. Often these rugs were woven in remote parts of the country and did not easily enter the market. The foreign buyer was unaware of them because they simply were not available. For example, in Turkey, Yoruk rugs had always been poorly represented in the bazaars vis-a-vis the products of the villages. In Iran, the townspeople preferred the carpets of Tabriz, Kirman, Keshan and Meshad, to what they consider the declasse weavings of the Qashqai, Kurds, and Afshars. A good example of traditional weavings which began appearing was the Bakhtiari kelims in the double interlock tapestry technique which have appeared in the market only in 1960s. In Afghanistan, Turkoman and Baluchi rugs were the main weavings marketed. The rugs presented here come from areas and ethnic groups where the Kabul rug merchants have been unaccustomed to buying and which they hold in low esteem.

The question arises, ‘‘Why are they appearing now?’’. O’Bannon believed the main reason is that rug dealers like himself have shown interest in the few which began to appear a few years ago. The rugs have been owned by the weavers or their families but until 1970s the Kabul rug merchants would not buy them. Further, many of the weavers lived in remote areas, were nomadic or semi-nomadic,were relatively unincorporated into the socio-economic-political life of Afghanistan, had held these weavings because of their utilitarian value, and, most importantly were unaware that they had commercial or trade value. Factors which have contributed to the breakdown of these constraints have been the development of a network of improved roads throughout Afghanistan, creeping economic development which has resulted in tribal settlement, exposure to manufactured goods to replace handmade products, a money as opposed to a barter economy, and lastly an influx of Western rug dealers in the 1970s interested in authentic nomadic and tribal weavings untainted in their manufacture by commercialism. These rugs filled the last requirement admirably and as a consequence the marketplace has responded.

It was mentioned earlier that these rugs are called Kyrgyz, Kazakh, Uzbek, Arab, Tatar, and Aimaq by the Kabul merchants. All of these tribes are found in Afghanistan but little is known about their crafts. Therefore, a precise determination of the actual sources of these rugs is difficult to make. O’Bannon’s information about them in Afghanistan has come from the merchants. To his knowledge, no one has conducted any firsthand, primary field research on these rugs among the weavers.

All of the names used refer to ethnic groups who are part of the population of Afghanistan. They also constitute major ethnic populations in the former Soviet Union as evidenced by the Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. The Uzbeks were the largest and one of the major ethnic groups in Afghanistan. They were primarily urban dwelling, but there were also agricultural and semi-nomadic Uzbeks. The Kazakhs were less numerous and include a similar range of socioeconomic lifestyles. The Uzbeks and Kazakhs were found throughout the northern parts of the country and in the major cities such as Kabul and Herat. The Kyrgyz people lived in the high mountains of the Wakhan Corridor and were almost entirely involved in pastoral nomadism. The Aimaqs were a conglomerate group of nomadic and semi-nomadic people in western Afghanistan. There were ethnic Arabs in Afghanistan and Central Asia who have been assimilated socially and linguistically by other ethnic groups such as the Uzbeks and Turkomans. With the exception of the Arabs and a segment of the Aimaqs, the term Tatar could be a generic reference to the other groups as they were the entire Turko-Mongol race which is referred to as Tatar. All of these groups were known to weave but little factual documentation of their weavings has been researched by the 1970s. Some of these people have been living in Afghanistan for centuries and others were newcomers after the Communist revolution in Russia. A question exists, therefore, about which of these weavings were woven by the indigenous Afghanistan groups and which may have been woven by the others either in Central Asia or after their arrival in Afghanistan.

For that moment – O’Bannon said, - one must rely on the sources referred to earlier. The secondary sources were the Kabul rug merchants and published materials. The Kabul merchants’ information was unreliable because their interest was purely pecuniary, and they have made no systematic effort to elicit ethnic, tribal, age, weaving area or dye source information from the sellers. Hence arriving at an attribution of type from this source was useful only as a cross reference and correlation with other data.

Published maternal on these rugs was extremely scanty. The only significant published volume is Moshkova’s The Carpets of the People of Central Asia, 1970 (in Russian). Although this volume contains discussions of the weavings of the Uzbeks of Samarqand, the Kyrgyz of Ferghana, and the Uzbek Tribe Turkoman, and none of the illustrated carpets were the same as those presented here. There were some designs which are shared with the Moshkova illustrations but minor elements and border patterns differ significantly. It is probable that these weavings are related but come from distinctly different regions and sub-tribal units which share a common heritage with those of Central Asia.

A second source, but one which relies heavily on Moshkova, Kabul rug merchants and some other Russian sources is Uzbek by D. Lindahl and T. Knorr. The weavings published by them are attributed to the Uzbeks. In general, O’Bannon agrees with their attributions and has expanded the type of weavings which he believed were of Uzbek origin.

Other published examples of these rugs were rare, but these few examples demonstrated the need for more information. In Gans-Rudin’s Antique and Oriental Carpets, he illustrates a piece which he calls a Beshire Turkoman. When compared to the cover example it is clearly of the Kazakh group. In the February, 1979 auction catalog of Lefevre, Plate 12 is attributed as ‘‘possibly Ersari, first half 19th c.’’ This piece too is a kelim of the Kazakh group. As his monograph was going to press the winter 1978 issue of Hali arrived carrying a report with illustrations of an exhibition in Germany of Arab and Uzbek rugs from northern Afghanistan. It is mentioned that the rugs were originally called Kyrgyz but through subsequent field work it was determined that they were Uzbek and Arab. The nature of the field work were not specified. The rugs labeled Arab, O’Bannon called Uzbek, and the rugs called Uzbek, he called Kazakh.

The only readily available primary sources are the rugs themselves. O’Bannon believed that it is possible to divide these rugs into specific, related groups based on structural, color and design features. From the rugs he had seen to date, two groups were emerging with well-defined characteristics. These two groups he chose to call Kazakh and Uzbek. In rationalizing the two categories O’Bannon had been guided by the characteristics of the rugs, correlative date in Moshkova, and names used by Kabul merchants whom he considers the most reliable. The comments of Dr. Nazif Shahrani had also been instructive. Dr. Shahrani, an Afghan Uzbek from Badakhshan Province, holds a PhD in Anthropology from the University of Washington in Seattle. His doctoral research was on the Kyrgyz of the Wakhan. Dr. Shahrani has confirmed the following facts about weaving practices of these various ethnic groups:

1. The Kyrgyz of the Wakhan do not weave pile rugs but do make flatweaves, felts and needlepoint.

2. The Kyrgyz collect and sell Yak hair to other groups for spinning into thread for weaving purposes.

3. There are Kazakhs in Afghanistan, some for many generations and others who came after the Communist Revolution in Russia.

4. The Kazakhs are found across northern Afghanistan as far west as Herat and in Kabul.

5. The Kazakhs weave pile and flatweave rugs.

6. The Uzbeks of Badakhshan weave only flatweaves, but it is possible that the Uzbeks further west in northern Afghanistan do weave pile rugs.

7. The term gadjari, which refers to a float warp technique of weaving, is a Kyrgyz word and is used by all other weaving groups in Central Asia.

Based on these facts, it is safe to assume that none of these pile rugs were woven by Kyrgyz, in spite of the attributions of the Kabul rug merchants.

There are several features of these rugs which set them apart from the weavings of the Turkomans and Baluchis, the best known rugs of Afghanistan. These features are colors, techniques, weaving materials used, and rug sizes.

A feature of the Kazakh and Uzbek large rugs was the use of excellent reds, blues, yellows, and greens. The yellows were truly remarkable for their strength and clarity. In the Kazakh group this results in some of the best greens seen in rug weaving. White and brown comes from natural wool or Yak hair. In the best of these rugs these six colors are exceptional in their purity and brilliance. Some pieces do contain less clear colors and the more recent pieces contain synthetic dyes in orange, purple, and lavender-blues. Some of the oldest pieces have small amounts of a bright red which is most likely an early aniline dye. This red is found in Salor, Tekke and Saryk Turkoman weavings of the same period. In general, the majority of the dyes used in these rugs are vegetable rather than synthetic.

One finds both the Turkish and Persian knot in the pile rugs. Several technical features were not found in other groups. These are:

1. Edges. In Kazakh pile rugs, if there is a selvedge, the weft threads connect the pile to the selvedge by enclosing only the first warp of the selvedge rather than being worked through all of the selvedge warps. In many pieces, particularly the Uzbek, there is no selvedge and no overcast.

2. Pile and knotting. The pile in most of the knotted rugs is long and shaggy and the knotting coarse. The pile threads are S plied rather than loose as in other rugs. Because of the coarseness of the pile threads, the ply has loosened in old pieces and can only be observed near the base of the knot. The knots are tied and cut by the weaver and a second clipping is not done. Knots may be tied on adjacent warps or may be tied around every other warp. This latter technique results in a very coarse fabric. The Persian knot is normally used for finer weaving and usually pieces woven in this knot are small and do receive a second clipping to make a uniform and shorter pile.

3. Wefts. The number of wefts between each row of knots may vary from 1 to 5. They may be plied or consist of two loose Z spun threads. Some of the Uzbek pieces have a weft under the row of knots in addition to between each row of knots. In this technique the design and knots are hardly visible on the back of the rug. Warp and weft threads are normally of the same diameter.

A unique feature of many of these rugs is the use of Yak hair for warp and pile. Yak hair is dark, lustrous, brown, and extremely durable. In the oldest pieces it is inevitably longer than the dyed wool areas. The presence of Yak hair is an indicator of age of a piece as well. The pieces which have been made within the last 20-40 years rarely have it. In more recent pieces it is replaced by brown wool.

The warp and weft of these rugs was usually a dark brown wool or Yak hair. It was of medium to coarse diameter which contributes to the low knot count of these rugs.

The wool used, although coarse, was highly lustrous and durable. In the oldest Kazakh and Uzbek pieces, id has an extremely high sheen which enhances the glow of the colors.

The utilitarian pieces such as the tentbags and tentbands were similar in size to the weavings of the Turkomans. The floor rugs, however, appear to be distinctive. Of the Kazakh rugs, there were two sizes. The long pile rugs, which were the largest, are typically between 45 feet wide and 8-9 feet long and woven as one piece. The short pile rugs were between 3 feet wide and 4 feet long. Flatweave rugs were long and narrow being typically twice as long or more than wide, e.g. 6’'x12'.

The Uzbek rugs were of two types. One type was a floor rug. They were in general 6 feet by 11 feet. They were woven in three strips which had been sewed together, two side border panels and the field panel. Yak hair was used for the warp and pile in these types. A second type was a long runner which may have been made as a bed or divan cover. This type was typically made of three strips which were sewed together although 4 or 5 strips were not uncommon. Cotton warp and weft were common in some of these pieces. White cotton was also used for the pile.

In general, O’Bannon had not seen a piece which he could comfortably date earlier than the last quarter of the 19th c. The majority were early 20th c. It was the weaving of these pile rugs ceased about 20 years ago. A few new kelims of a type similar to the picture below were being woven, but synthetic dyes are being used and the color sense was entirely different from the traditional, vegetable dyed ones illustrated here.

The oldest rugs of these types have the following characteristics:

1. Colors. The six main colors—red, blue, yellow, green, ivory, and brown—in pure tones are used. The brown would probably be Yak hair.

2. Wool quality. The pile has a high sheen and is exceptionally lustrous.

3. End finishes. In the Kazakh large rugs there are kelim ends from 6 to 9 inches wide which are usually red with yellow stripes and occasionally blue stripes.

4. Wefts. Dyed wefts in yellow, blue, red and green may be found in the oldest Kazakh rugs. In Uzbeks rugs, the ones without cotton for warps, wefts, and pile are probably the oldest.

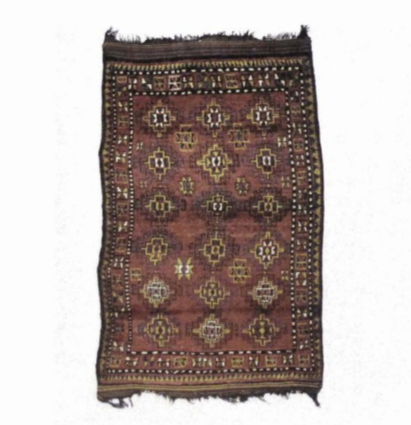

The Kazakh group represents a very complete set of weavings. It includes both floor rugs and utilitarian weavings in pile and flatweaves. These weavings in design, materials, colors and variety of utilitarian pieces are indicative of a nomadic group. The pieces illustrated include the following:

A. Pile Rugs 1. Short Pile 2. Long Pile

B. Flat Weave Rugs

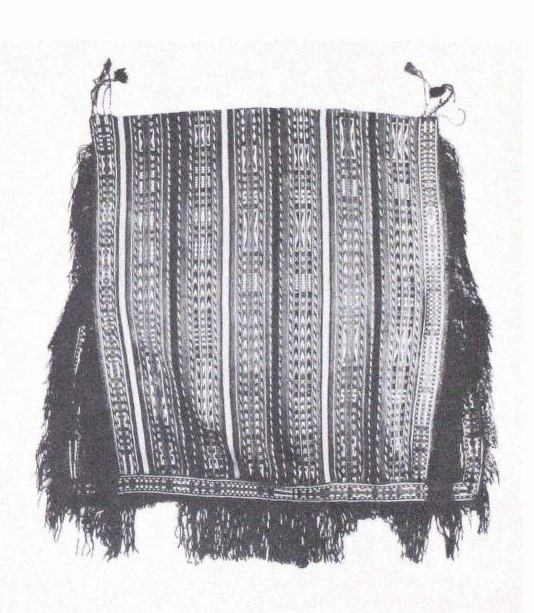

C. Carrying Bags 1. Pile 2. Flat weave

D. Flat Weave Utilitarian Pieces 1. Tent bands 2. Horse covers

Although both the Persian and Turkish knot were used, there was a tendency to use the Turkish knot with long pile rugs and the Persian with short pile rugs.

In the flatweaves two techniques were used. One was the kashkari weave, which was called double interlock tapestry. It was a rarely encountered technique. It was used by the Bakhtiari and Lori tribes in Iran, but was not used extensively by other groups. On most pieces with this technique the back of the piece was finished rather neatly with few loose hanging threads. However, it was not uncommon to find numerous loose threads that were long and dense creating a shaggy back on some pieces. It is possible this was done deliberately so as to create a pad and insulator in cold climates.

The gadjari technique was a supplementary floatwarp face tapestry. In this type of weaving two or three sets of warps are employed. The face of the piece was flat and contains a clear set of geometric designs. The back shows no distinct pattern because the sets of warps are exposed. Weavings in this technique are composed of bands 1 to 15 inches in width. The bands are usually about 40 feet long and are cut into the desired lengths and sewed together to create rugs, covers or horse covers. Typical colors of these bands are red, yellow, green, white and blue. The white may be cotton or wool.

The designs of Kazakh rugs were totally geometric. However, the number of designs used for the field and borders is rather limited. On large rugs the design was a latch hook polygon with a star in the center. The colors used for these were normally used on a diagonal although a few with a vertical color axis have been observed. The main border usually consists of large stars set within squares. On smaller rugs and bags there are more designs employed. The number of borders also is greater. One can see some design relationships between the designs of the short pile bags and the flatweaves in kashkari technique. The designs used in the gadjari technique are more complex and unrelated directly to the other weavings.

The colors used in Kazakh weavings usually are six: red, blue, yellow, green, white and brown. The yellow may go from pale to gold; the green from a lime green through dark green to blue-green; the red from mid red to dark; the brown if mid brown in tone is probably wool, if a dark brown it is probably Yak hair; and blue is typically a mid to dark blue. In more recent pieces one can find oranges and purples which are most likely synthetic dyes. A pink to magenta red occurs only rarely. Typically the colors of these rugs are primary and have a clear intensity. The silky lustrous wool of the older pieces heightens the clarity of the colors.

If the Kazakh rugs reflect a nomadic society, the Uzbek rugs are more reflective of a settled people. These weavings are primarily floor rugs or long runners which appear to have been made as bed or divan covers. There are no utilitarian pieces such as donkey bags, large carrying bags, saltbags, etc. The Uzbeks weave both pile and flatweave rugs. Only the pile weavings are illustrated. There are kelims from Afghanistan which are referred to as Maimana kelims which are woven by Uzbeks.

There are two distinct types of pile rugs in both design and materials. The first type of rugs are large floor rugs typically 6 feet by 11 feet. They are made in three strips which are sewed together. The center strip contains the field designs and the end borders. The side borders are additional strips which are sewed to the center panel. This type of rug may have Yak hair in the pile and for the warp threads. The design of the field is latch hook polygons similar to that found in the large Kazakh rugs. The wools are lustrous, the pile long, and there 1s no selvedge or overcast edge. The colors are a dark red, a bright red, yellow, blue, white, brown and occasionally a blue-green.

The second type of rug is a long runner. In this type two or more bands are woven and then sewed together. They differ from the large rugs because the field designs are not woven as a separate unit with the borders attached. The field area is usually matched in the center. The border design may be in the same strip as half of the field design or it may be an additional strip. The designs vary from diamonds to complex forms or to no design at all. They very in width from 2 to 3 feet and in length from 8 to 12 feet. Usually there is no fringe or kelim finish although the unpatterned ones do have braided fringes occasionally. The colors used are much more varied and range from light to strong intensity. Vegetable dyes are common in many of these pieces but there are also synthetic dyes in many of the later pieces. Warp and weft may be wool or Yak hair as well as cotton.

The knots and wefts of both of these rugs are unusual. The Turkish knot is used but it is tied around alternate warps and with a warp left between each knot on the horizontal. There is a single weft between each row of knots but there is also an additional weft under each row of knots. This results in a very low knot count. The design is not visible on the back of the carpet because the base of the knot is almost entirely covered by the additional weft.

Two rugs not clearly belonging to either the Kazakh or Uzbek group have been included to illustrate some variations which exist within this group of rugs. In design and technique they differ from these two groups. However, they are quite clearly related. They may represent unique pieces or the products of a weaver who decided to do something different. They do show that there is great variety in this newly emerging group of rugs and that much more is still to be learned about them.