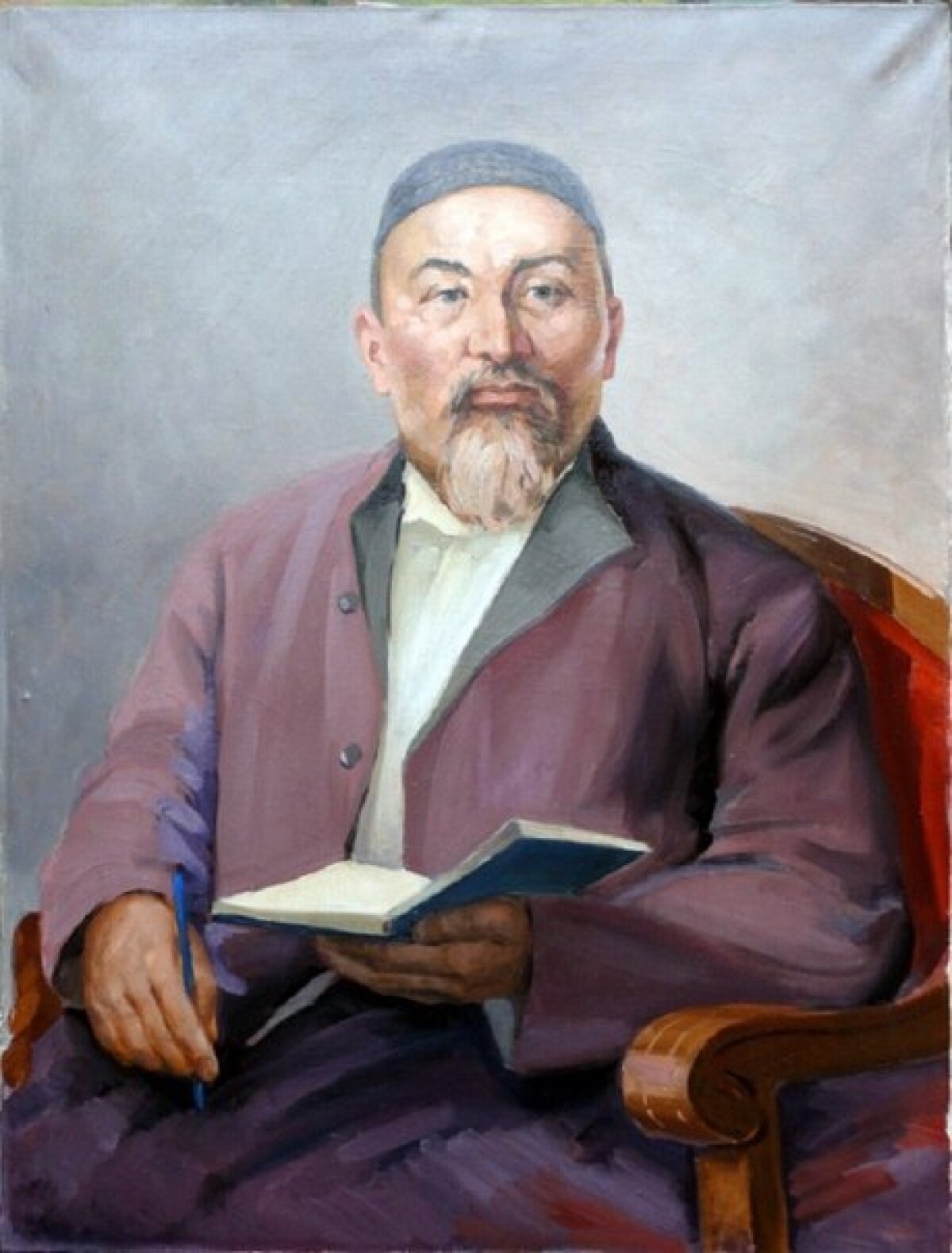

Abai Qunanbayev is an outstanding poet, composer, philosopher, thinker, educator and democrat, the founder of the new Kazakh realistic literature.

Abai's poetry is rich in content; it is distinguished by the problematic themes. These are poems on socio-political themes, satirical poems, philosophical reflections, landscape lyrics, poems about love, friendship, poetry, science. Lyric of Abai acquaints us with his reflections on the meaning of life, about the happiness of man, with his moral ideals.

Abai's time is complicated and troubled. This time was marked by the formation and further development of national realistic literature, the founder of which was Abai Qunanbayev.

Abai (Ibrahim) Qunanbayev was born in 1845 in the Semipalatinsk region, among the blue Chingis Mountains, in the family of the head of the tribe Tobykty. Akyns and storytellers brought up in him a sincere love for his native people, their history and rich cultural heritage. From the mother, he inherited a kind heart, in which every day grew outrage against violence and evil.

Abai's father, Qunanbay, was the leader of the Tobykty tribe. After receiving the initial education at home from the mullah, Abai was sent to the madrasah of Semipalatinsk Imam Akhmet-Riza.

Sent by his father to the Semipalatinsk madrasah, Abai, breaking its strict laws, seeks to learn Russian. Only three months continued his teaching in the Russian parochial school.

At the insistence of his father, thirteen-year-old Abai returns home to take part in the political life of the Steppe. Father began to gradually prepare for judicial and administrative activities of the head of the tribe. Abai comprehends the methods of conducting verbal contests, where weapons were honed eloquence, wit and resourcefulness.

The trial was conducted on the basis of the existing customary law of the Kazakhs for centuries. Drained into the affairs of tribal disputes, Abai delves into the most complicated mechanism of the social life of the Kazakhs. At the same time he manages to study Russian colonial orders, to learn European values. He comes to the idea of the inevitability of the end of the traditions of the Kazakhs and the transition to more progressive ones, connected with the introduction of bourgeois, capitalist principles.

Only after fifteen years did Abai return to the city to deepen his knowledge and become a champion of justice, a defender of the poor and oppressed. He eagerly studies the works of the classics of Russian and Western European literature, gets acquainted with the advanced Russian people exiled by the tsarist government to Semipalatinsk.

Abai was the bearer of a new concept of life, stood head and shoulders above the environment that gave birth to him. The Enlightener wanted to see human society a good and intelligent, progressively developing. The desire for the progressive development of society, where man is elevated by "reason, science, will," is one of the main directions of Abai's whole creative work. All the work of Abai is permeated with ideas of irreconcilability to idleness, false shame. The human character, in his opinion, consists only in the struggle against difficulties, in overcoming these difficulties.

As a result of the colonial policy of tsarist regime and the intensification of oppression in the second half of the 19th century, the situation of the Kazakh Sharua worsened. Caring about this part of the Kazakh poor, Abai pointed out to them the way to existence, urging them not to be shy of hired labor, as a more progressive form of labor activity.

Abai protested against intergenerational strife. He sharply criticized the vain, self-seeking rulers, cunning biys, and the morals of the ruling strata of society.

In the poem "Oh my Kazakhs, my poor people," the poet with pain in his soul says that in the steppe there is no unity, order, everywhere discord, because of money and power, feud turns violent.

He placed great hopes on young people; he turned to those who "were penetrating and sensitive in heart". The theme of enlightening the people in Abai's work has acquired a huge social sound. In disseminating knowledge, the poet saw a means of freeing people from social evil.

Abai deeply believed in the creative forces of the masses and understood that under the current conditions of public life the masses do not have the opportunity to fully enjoy the fruits of their labor.

Abai, when he raised the issue of ways to change society, believed that reforms, primarily education and science, can change the existing system.

Pushkin and Lermontov were the most beloved poets of Abai. He was worried about truthfulness, high skill, and life-affirming power of their works. Abai seeks to introduce the creativity of these great Russian poets to the inhabitants of Kazakh auls, and in the 1880s he began to translate excerpts from the novel by A.S. Pushkin "Eugene Onegin" and poems by M.Yu. Lermontov.

The study of Russian classical literature ideologically and artistically enriched the work of the Kazakh poet; he organically absorbed its enlightenment and aesthetic ideas.

But at the same time, Abai's creative work remains original; he is deeply national poet and philosopher. The subject of his poetic descriptions and philosophical reasoning was the life of the Kazakh people. We see him as an artist, deeply, truthfully and brightly depicting everyday life, customs and character of Kazakhs.

Abai died in 1904. During the life of the poet, his separate poems were published in the years 1889-1890 on the pages of the newspaper Dala Ualayaty (Stepnaya Kirgizskaya Gazeta), published in Omsk. The first collection of Abai's poems was published after his death in 1909 in St. Petersburg. Abai's works were translated into many languages of different peoples.

The great son of the Kazakh people, Abai Qunanbayev, left a legacy of beautiful works. They embodied his whole life, his dreams of a bright future. His fiery verses and wise "Words of edification" will never lose their strength and freshness.

Translated by Raushan MAKHMETZHANOVA