The organization of schools was caused by the need for the tsarist government to prepare people for the administrative apparatus in the Kazakh province.

So, at the end of the XVIII century the organization of "garrison schools" in the near linear areas began. In 1789, the "Asian School" was opened in Omsk, preparing interpreters and clerks, in 1813 - a military school, converted in 1847 to the Siberian Cadet Corps; in 1825 Orenburg military school was created, also converted in 1844 in the Orenburg Cadet Body.

In all these schools, except Russian, the children of the Kazakh nobility were trained. As noted in the decrees, the schools were supposed to "promote the rapprochement of Asians with the Russians, inspire the first love and trust in the Russian government and deliver the edge of enlightened people."

In 1841, a school was organized at the Khan’s rate, which was also hosted mainly by children of the Kazakh nobility. In 1850, the Orenburg Border Commission opened a school, which, as it was said in its charter, was preparing "able people to engage in border management of the places of the clerks under the sultans-rulers and commanders in the Horde, as well as to correct other posts for which appointed Kyrgyz".

The school was seven years old. The program provided for the study of Russian and Tatar languages, geography, arithmetic, Muslim doctrine, compilation of business papers in Russian and Tatar.

With the development of capitalist relations in Kazakhstan, a large number of educated people were required. Russian-Kazakh schools, opened in the first half of the XIX century, adapted to the requirements of the colonial policy of tsarism.

Under the new conditions, tsarism was not interested in developing the education of the oppressed peoples. The instructions issued by the Ministry of Education indicated that "public education on the outskirts of the Russian state is a kind of missionary work and missionary is a kind of spiritual war."

The organization of public education in Kazakhstan was led by Russian missionaries, such as N. Ilminsky, A. Alektorov and others.

N. Ilminsky developed his system of enlightenment of non-Russian peoples of Russia. He considered the ultimate goal of education: "The encircling of foreigners and their perfect merging with the Russian people by faith and language." For this purpose, he proposed to open elementary schools for Kazakh children in their native language. In such schools, the Russian language was to be intensively studied. According to Ilminsky, the teachers should be trained people from among the Kazakhs.

Il'minsky wrote in 1885: "For us, it would be good for a foreigner in the Russian conversation to get mixed up and blush, write in Russian with a fair amount of mistakes, and afraid not only the governors, but all the chiefs."

No less indicative is another document, a letter from one senior official to Orenburg military governor Count Sukhatelin: "I'm not attracted to the hyperbolic desires of philanthropists to organize Kyrgyz people (Kazakhs), enlighten them and elevate them to a degree occupied by European nations. I whole-heartedly wish that they never sowed bread and did not know not only science, but even crafts."

Ilminsky adhered to the principle of teaching the Russian language by comparing the Kazakh language with the Russian, suggesting that the Arabic alphabet should be replaced by the Russian language so that the student of the Kazakh school could easily read Russian books, but could not read religious literature. In the school curriculum, he included Orthodox faith. Despite the reactionary goals, the Ilminsky system contributed to the spread of Russian education among Kazakh children. It was the graduates of such schools that formed the core of the young Kazakh intelligentsia. Most of them subsequently openly opposed the introduction of the missionary system.

At the end of the XIX century in many cities, villages and auls opened a lot of schools; it was the beginning of polytechnic and women's education. Many schools had boarding schools. By this time in Kazakhstan there were more than 100 two-class schools with a contingent of over 4 thousand students.

More capable graduates of Russian-Kazakh schools entered the cadet corps and universities of Russia and foreign countries. Omsk and Neplyuev cadet corps prepared from among the Kazakh youth officials of the local colonial apparatus. A large number of Kazakh boys studied at the St. Petersburg University, Military Medical Academy, Kazan, Tomsk universities and other higher education institutions.

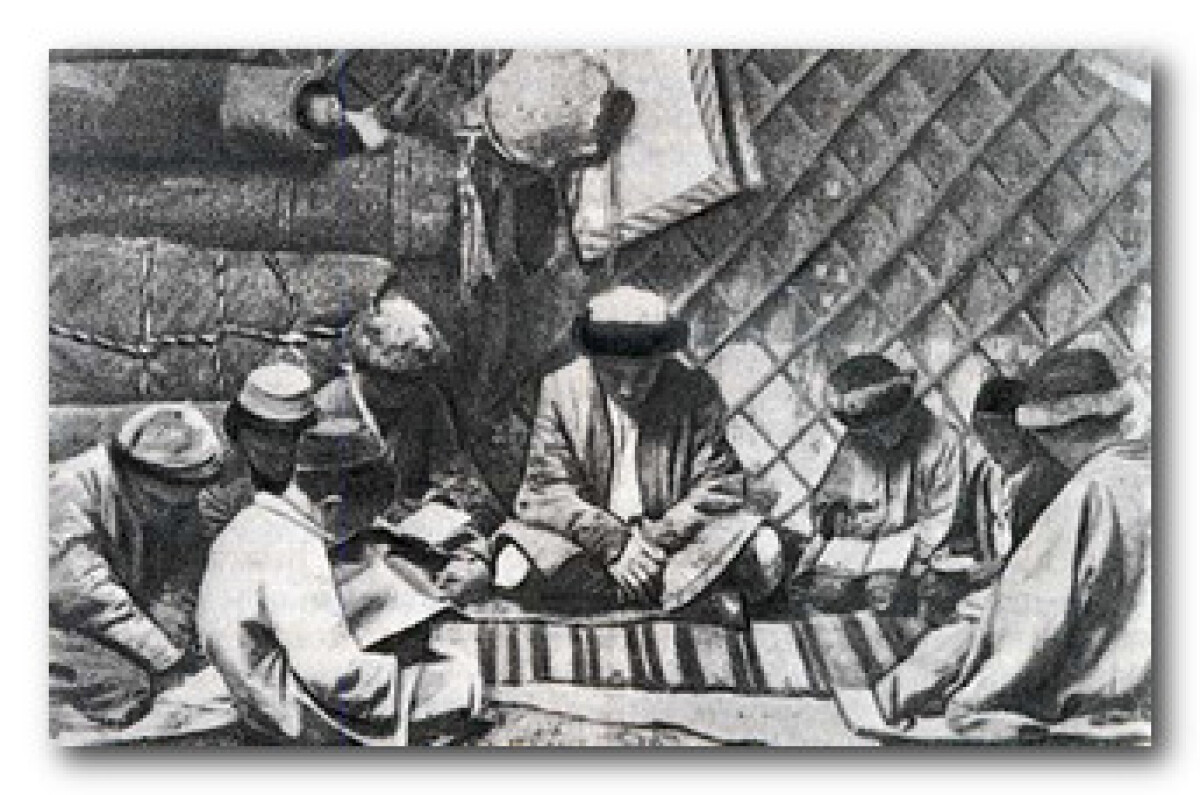

Traditional education was further developed. In the Kazakh family, 5-6 years old boys and girls were trained at home, and then they entered three-grade schools, where they studied grammar and arithmetic. The curriculum of the madrasah included such subjects as Arabic philology, religious law, and religious philosophy. The pupils also studied general subjects and the basics of medical science.

Madrasah was kept at the expense of private individuals. The state allocated a meager amount for the development of education. Madrasah had several darischanas (classrooms), hujras (student rooms), and rooms for ablutions, dining rooms and kitchens. The pupils were called shakirs, the teachers were called mudarries. On a post of the teacher accepted people not younger than 40 years, having the diploma of madrasah. They received in the year up to 700 rubles. The academic year began in September-October and ended in May-June.

In schools and madrasah studied children of not only wealthy parents but also the poor.

Prominent statesmen S. Asfendiyarov, S.D. Zhandosov, T. Zhurgenov, S. Mendeshev, T. Ryskulov, N. Torekulov, I. Omarov and others made a definite contribution to the development and formation of the republic's pedagogical thought, the classics of Kazakh literature M.O. Auezov, S. Seifullin, I. Jansugurov, B. Mailin, S. Mukanov, G. Musrepov, G. Mustafin, people of art and science A. Zhubanov, S. Amanzholov, E. Bekmakhanov, M. Gabdullin, S. Zhienbayev, Kh. Zhubanov, K. Jumaliev, A. Margulan, M. Sarybayev, K. Satpayev, N. Sauranbaev, D. Tursunov, M. Khamraev and others.

Translated by Raushan MAKHMETZHANOVA

Use of materials for publication, commercial use, or distribution requires written or oral permission from the Board of Editors or the author. Hyperlink to National Digital History portal is necessary. All rights reserved by the Law RK “On author’s rights and related rights”. To request authorization email to kaz.ehistory@gmail.com or call to (7172) 79 82 06 (ext.111).