On March 1, Kazakhstanis celebrate the Day of gratitude, in memory of the support provided by Kazakhs to the peoples deported to the Kazakh steppes. Dozens of peoples, including Jews, became victims of Stalin's totalitarianism. Israeli Ambassador to Kazakhstan Edwin Nathan Yabo Glusman thanked the Kazakh people for supporting the Jews during the war. He noted that there is no doubt that Kazakhstan has become a haven for many peoples, including Jews. The modern Jewish community of Kazakhstan, for the most part, consists of subsequent generations of those people who escaped here from the horrors of war. Kazakhstan admires and surprises with its patience, openness, and kind attitude towards everyone, both refugees and prisoners. Thanks to the Kazakh people, both children and adults found salvation here and found a second homeland.

Speaking of gratitude, the Jewish people remember first of all those who helped to avoid the Holocaust. During the Second World War, more than 6 million Jews died in Nazi camps. In memory of this heinous crime against humanity, UNESCO has established the Holocaust Memorial Day (Shoah), which is celebrated on January 27. Jews are especially grateful to the many diplomats who, despite all possible restrictions, saved people in their diplomatic work during the Second World War, risking not only their careers, but also their lives. Yad Vashem has created the title "Righteous of the World" especially for such selfless people.

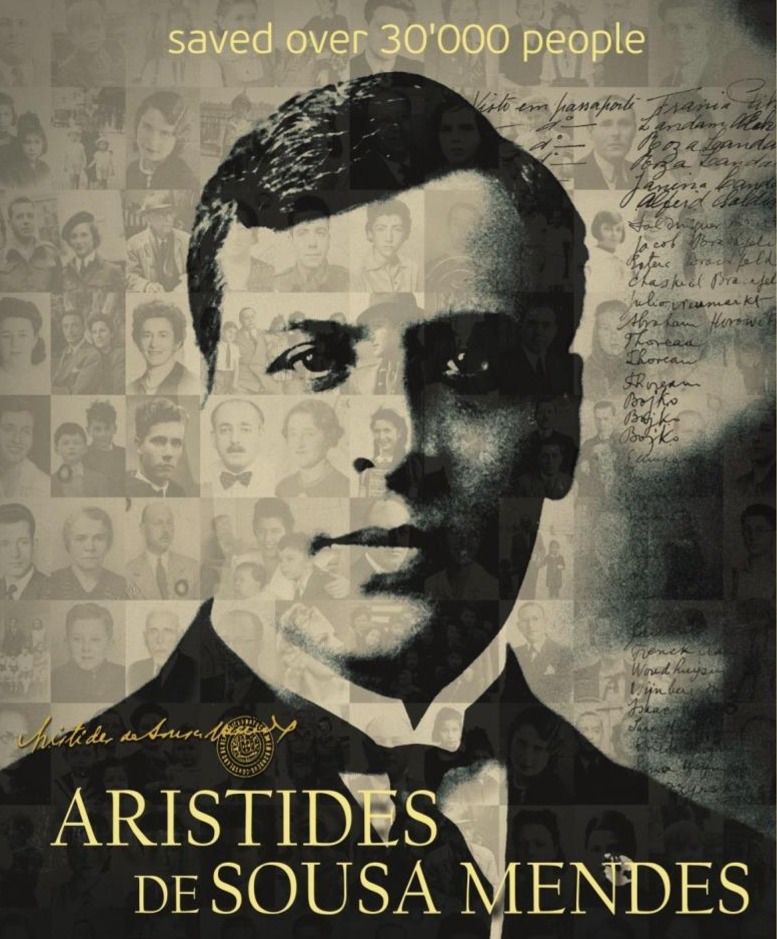

Mr. Edwin Nathan Yabo Glusman spoke about the Portuguese diplomat Aristides Souza Mendes, who is a righteous man of the world and saved the lives of many Jews. By a wonderful coincidence, this diplomat turned out to be an ancestor of the Portuguese Ambassador to the Republic of Kazakhstan, Mrs. Maria Fatima Mendes.

Mr. Ambassador told stories about the difficult tortures of choice faced by ordinary people.

Impossible solutions

How to describe the gigantic scale of the Shoah, because it is not enough to mention the number of victims, more than 6 million. This number is impossible to cover, it's huge, it's just a number.

Perhaps by mentioning the staggering number of children killed during the Shoah (Holocaust) - one and a half million - we can get an idea of the genocide. But this is another huge number that is not easy to accept.

We also try to tell the story of an individual, as if to look the Holocaust in the face, someone with whom we can not identify ourselves, for example, Anne Frank. Or we are talking about the Yiddish culture, which was destroyed and is practically an anthropological relic.

However, there is a fact that makes you feel the scale of the genocide: if we observed a minute of silence for every victim of the Holocaust, the silence would last 11 and a half years.

However, the impossible decisions of both Jews and non-Jews during the Holocaust can add to the picture of the tragedy of the Holocaust and the moral bankruptcy of humanity at that time. Dilemmas that someone only faces in extreme, extraordinary situations and in a brutal reality where a simple choice means life or death. Extreme dilemmas that were common during the Shoah. These impossible solutions are able to highlight, concentrate and convey the dark feeling of the Shoah.

Your choice

Esther Frenkel was a teenager who worked as a secretary in the Lodz Ghetto Judenrat in Poland. The Judenrat was a Council of Jews created by the Nazis to manage the ghetto. Among other functions, this council was responsible for selecting people to be relocated, euphemistically speaking, according to figures provided by the Nazis.

In September 1942, the Nazis ordered the deportation to the ghetto of all those who could not work, children, the sick and the elderly.

The Nazi ghetto director came to the council's office and handed Esther Frenkel a form to register the names of 10 people who would be exempt from deportation. At that moment, this teenager had to decide who would live and who would not. How do I choose the right names?

Esther Frankel moved as quickly as she could, filling out a form on her typewriter for the officer to sign on the spot. What could she have done? She had a family, she had an uncle, so she had to save him. She also had a cousin… After adding the names of her relatives, there were extra empty spaces, she entered the names of her neighbors, entered the name of another friend who had a small daughter. I wrote the names of the children of a neighbor in my hometown who used to come to their home. Esther Frankel has never denied that she used her privileged position to save her family, but the despair of mothers of deported children has accompanied her all her life. Be that as it may, the Lodz ghetto was liquidated in 1944, and all the people were deported to death camps.

Angela and Frantisek Melo and their son

Before the war, the Lamm family owned a farm in Nitra, Slovakia, where they had sixty workers. František Melo worked there. With the Nazi invasion, all Jewish property was expropriated, and overnight the Lamm family was left on the streets with no means of support and no rights.

František Melo did not abandon his former employer and offered him his house as a shelter. It should be remembered that during the Nazi occupation, defending Jews was a crime and was punishable by death.

One day in 1944, Nazi soldiers and Slovak collaborators arrived at Melo's house and found nothing and no one, but before they left, they ordered the Melo couple's son to report to the village police station the next day.

That evening, a dramatic discussion took place in a modest house. It was clear that if their son didn't show up the next day, the soldiers would return. In an era of few miracles, a Jewish family can be found by repeated search. On the other hand, it was also clear that the young man was going to be harshly interrogated.

The Lamm family might be better off leaving the house, but where would they go? After this painful discussion, the Melos decided that the Jewish family would not leave the house, and their son was brought before the Nazis the next morning.

Despite the brutal interrogation, the young man did not reveal the whereabouts of the Lamm family, who remained in Melo's house until the end of the war.

In 1979, three members of the Melo family were recognized by the State of Israel as Righteous among the Nations.

The Resistance Dilemma

The difficult circumstances of life in the ghetto forced its inhabitants to fight for survival on a daily basis. Thousands died of starvation, cold, and disease. Physical survival was the main and daily task for ghetto residents. To join the armed struggle, titanic efforts were required. Most of the ghetto residents, including children, the sick and the elderly, were unable to take up arms.

Those who chose armed resistance had to mobilize virtually nonexistent resources to act beyond basic physical survival. However, if you look closely at the terrible moral and ethical dilemmas they faced when they took up arms, you can see that these dilemmas were a real challenge.

Could those who supported the armed resistance have escaped knowing that they were endangering their families, their communities, because of the collective punishments carried out by the Nazis? Should they fight despite the fact that a part of the ghetto population was opposed to armed struggle? Could they afford to fight, knowing that the resources allocated to a lost battle could be used to save Jews inside and outside the ghetto?

In one case, an SS commander in the Radoszkowicz ghetto identified a fugitive and forced the fugitive's father to choose one of his other two sons for execution. If he refused, he threatened to kill both of his sons. My father decided to do the impossible and made a choice. That same night, he hanged himself. It was probably an easy choice.

Lifetime visas

In 1940, Aristides Souza Mendes was the Portuguese consul in Bordeaux, France, located on one of the main routes of one of the largest movements of people in European history. How to proceed? Issue as many visas as possible? Should he ignore instructions from Lisbon to save lives? Should he condemn his family of 15 children to poverty because of his decisions? The exertion caused him to have a nervous breakdown, and he spent some time in bed. His religious and ethical beliefs brought him out of a state of nervous breakdown, and his phrase has come down to us, one of those phrases that warms the soul: "I would rather stand with God against man than with man against God."

A teenager deciding who is saved and who is condemned is also a Holocaust tragedy. The night spent by parents knowing that their son will be tortured the next morning is also a Holocaust tragedy. The moment when the father must choose his son for execution is the Shoah tragedy. A nervous breakdown and the resolution of Aristides Sousa Mendes ' ethical and moral dilemmas is the tragedy of the Shoah.

After being recalled to Lisbon by the Portuguese authorities, Aristides left Bordeaux in his huge family car, protected as yet by diplomatic immunity. At home, he faced an internal investigation, bureaucratic procedures and dismissal from the diplomatic service. Later, his family was supported by the Jewish community of Lisbon, and his children were sent to different countries, mainly to Canada, the United States (and Switzerland), because they were not accepted to continue their academic and professional life in Portugal. Aristides Souza Mendes died in April 1954.

Ambassador Aristides Souza Mendes received the title of Righteous among the Nations in 1966. Other diplomats from Sweden, Switzerland, the Czech Republic, France, Chile, Romania, Turkey, Japan, Ecuador, Brazil, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Poland, the United States, the Vatican, China and other countries were also recognized.

In conclusion, Mr. Ambassador thanked Mrs. Maria de Fatima Mendes for the noble actions of her family member and expressed his deepest respect and admiration for the Portuguese diplomat Aristides Souza Mendes.