Compared with the previous periods in the history of Kazakhstan, this period is illuminated by the written sources. In comparison with the previous time, the number of cities mentioned in the sources declined to 20, and settlements dating from the second half of 15th and beginning of 18th centuries — to 23. There are no names of North Karatau’s cities, Urosogana, Sugulksnta, Kumkenta, mentioned in written sources in the second half of the 15th century. Settlement (Jan-kala) Kiz Kala stopped existing in the lower reaches of the Syr Darya; rural settlement Buzuktobe (Chilik) — on Bougouni, Kuyruktobe and Oxus — in the Middle Syrdarya.

Compared with the 9th—12th centuries, the number of cities of South Kazakhstan known from the written sources has dropped by almost 3 times and the number of settlements by 6 times.

From the middle of 15th century, Otrar’s suburb becomes empty. So in the 16th century, its territory was not bigger than a hectare and city life was only concentrated in the central part.

Reducing of urban area was noted for Sairam, Signak, Uzgenta, Suzak. Rabads are emptied and the entire urban life is concentrated now within the central, most fortified part of the city. In the 16th-17th centuries, cities of the left bank of the Syr Darya, such as Arkuk, Kudzhan, Akkurgan, Uzgent, began to play a greater role in the political and economic life of the region. On the northern slopes of Karatau the role of the main city passed to Suzak. There is a rapid rise of Iasi-Turkestan to the rank of capital of South Kazakhstan.

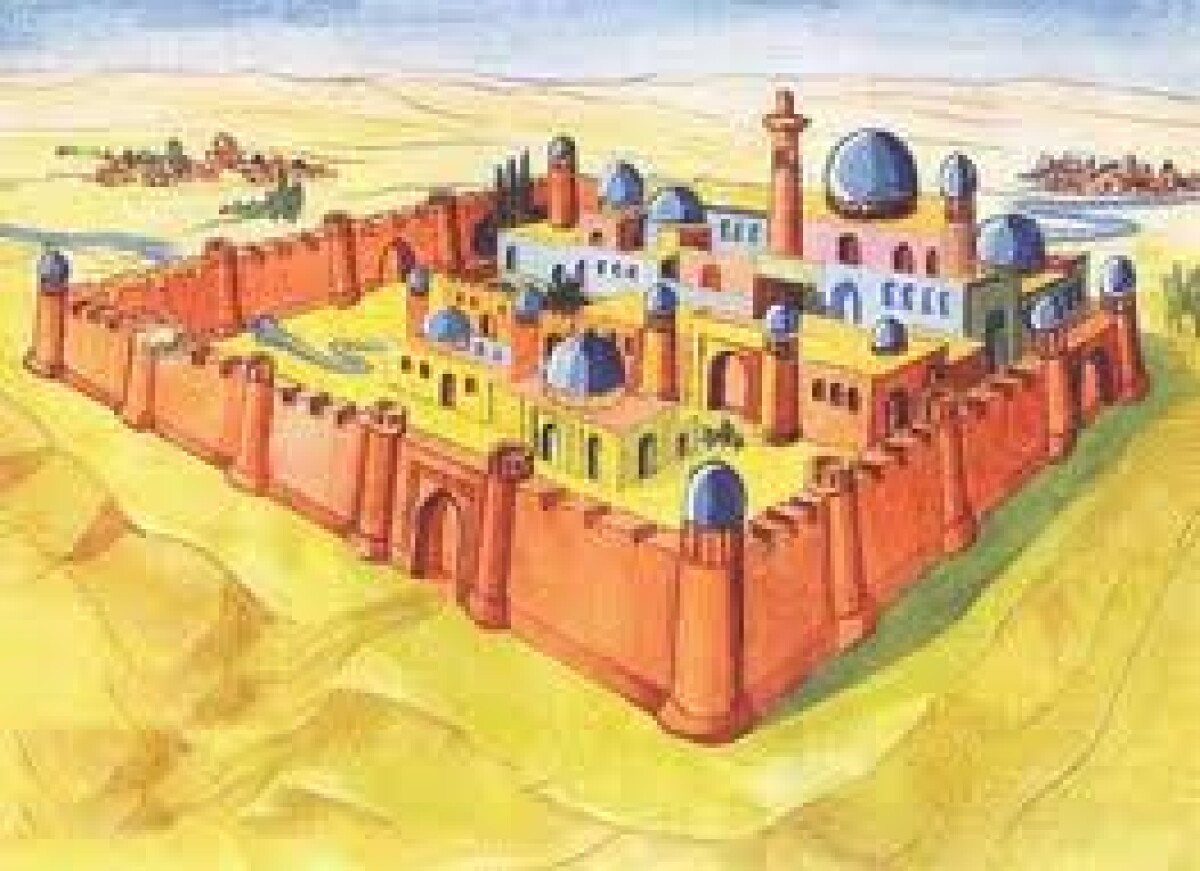

Almost all of the late medieval cities of Kazakhstan inherited a planning hull of the cities of the previous time. In the topography of the late medieval cities, “hisar” — the central walled part of the city, and suburban areas are distinguished. The term “hisar” is understood both as a “city”, “fortification”, and as “the city wall.” Hisar “is a densely populated part of the fortified town, in which government buildings, military barracks, mosque, the main markets and handicraft shops, houses of the city’s main layers are located.” The territory behind a wall of hisar was suburb, rural area, and the life was drastically different from the life of Hisar, mainly city. Street network constituting the skeleton of the city was quite difficult. In Otrar, for example, were recorded not just the central highway connecting southern and northern entrance, but also six through streets, marching in the meridional direction.

The central main street linked the northern and southern gates. The ring road encircled around the perimeter of the city immediately behind the wall. The ring road also had exits from the town that were made later.

There were discovered more than 30 blocks of 16th-17th centuries in Otrar. Each consisting of 6 to 12 houses; the area of the block, on average, was no more than 1,500 square meters, and the average number of houses in the neighborhood was 11. Intra streets, width up to 2 m, started from the main streets, and united all homeownership of the block. They tend to be unpaved, had a dense, compacted surface. As a beautification causeways of the street in front of the houses sometimes were used and blind areas along the street made of brick and rubble. Streets had “pockets” — extensions apparently served as a shelter for cattle. Sometimes in-block street crossed into the area-patio that had a series of household pits, and more often a patio was used as a corral by all the inhabitants of the block.

Social picture in blocks, reconstructed on the basis of archaeological materials (as noted for an earlier time), was homogeneous. There were no blocks of the “rich” and “poor.” Each block has 2-3 large multi-room houses, 1-2 small one-, two-and three-bedroom houses and the others that are about the same in size. This is explained by ethnographic parallels. In XIX century Bukhara, for example, in the same block, in the same block community lived both rich and poor people. Moreover, social inequality did not violate the established structure of everyday life since ancient times. On the contrary, for the rich and noble families, this kind of neighborhood represented a lot of amenities since it was easy to find people for services.

What is interesting is the specialization of blocks by the sort of activity that people in that neighborhood were doing. There was only one block in Otrar that could be defined as a “block of potters”. Specialization of its residents has been the traditional potters and passed down from generation to generation.

Among the public buildings in the city structure, as before, there were public baths.

During the bitter struggle between the rulers of the steppe for possession of Syrdarya cities, in which cities themselves suffered most of all, each of them must have had a powerful system of fortifications. So it was not an accident that city walls, their height and inaccessibility, the depth of trenches were so vividly described in the writings of late medieval historians.

The remains of the fortifications of Sauran are still very impressive. Sauran’s wall built of adobe blocks, alternating with a clutch of adobe bricks. The preserved height of the wall is still reaches 6 meters. The remains of four round towers are traced on the wall. Behind the wall was a ditch depth of 3 m, a width of 20 to 50 m.

Twenty-meter narrow passages formed by the protruding segments of the walls led to the gates.

Powerful enough, judging by the excavations, were late medieval fortifications of Turkestan.

Buildings of 16th-17th centuries continue the development of the home of the previous time.

Compared with the housing of the second half 14th — the first half of the 15th centuries there are some new elements in the interior design of the rooms. Tandyr is transferred from the far corner near the entrance. The site tashnau “pulls” the second room, patio or quince, or living quarters and storage. Tashnau is not necessarily belonging of dwelling, it is also in store rooms and backyards. Sufa, which occupies most of the central area of the residential premises, raised off the floor by 30-40 cm. Tandyr with the mouth coming out the edge sufa is smudged into the sufa. Chimney begins with a round hole in the wall of the tandyr, it continued in sufa on the shortest section to the wall or corner. The chimney was connected with vertical wells in the wall of the house. Tandyrs are closed by lids. At the corner of sufa, usually in front of the tandyr, was arranged a rectangular drawer unit, a platform for coal incinerator. In the general interior of the room, tandoor and area of tashnau in front of it forms the economic zone. Here at sufa, near tandyr earthenware crockery is usually put. On board or site of tashnau there are millstones from the mill hocked. Sometimes in central room near the angle was a slit-like cellar. Within the walls of the room were arranged niches for storage of utensils. Sufas were covered by woven reed mats or ences, on top of which felt mat, cotton blankets were put. Prints and decay of mats and pieces of felt mats and quilts were found during excavations.

Storerooms with compartments were intended for storing grain, liquid and solids. In some houses there were patios, covered with awnings. Among the patios there was also iwan opened to the side of intradistrict street. It was possibly used as a corral.

Demographic estimates made for Otrar of the end of 16th— 80th years of 17th, which can be extrapolated to other cities are dominated in determining the amount of the urban population in each of the settlements and the whole region of the late medieval period.

The area of the residential neighborhood of Otyrar was from 1200 to 1300 sq. m. (average 1500 sq. m.). The territory of the city of 16th-17th centuries was 20 hectares or 200,000 sq. m; the fourth part of Otrar was occupied by public buildings, squares, and main streets. Therefore, the remaining area of 150,000 square meters was occupied by 100 residential areas. Each block contained between 6 and 12 houses belonging to the individual family, the composition of which, according to popular belief, was 5-7 people.

Each block had in average from 45 to 63 people; overall there were 4500-6300 individuals in the city or in average 5500 people. The same amount lived in Sygnak and Suzak.

In Turkestan lived 1980 people. Suran was 2 times bigger than Otrar so there had to be 11000 people livening there. Sairam had 7560 inhabitants, and overall in the centers of vilayets inhabited by just over 44,000 people. In Karasamane, Icahn, Karnak, Karachuke, Syutkente, Arkuke, Kotans, Uzgente, Ak-Kurgan lived from 1500 to 2000 residents. And in Yagankente, Suri, Yunkente, Kudzhane, Karakurune and unidentified settlements like Ran lived from 800 to 1,000 people.

Thus, the number of urban population in Kazakhstan during the 16th — the first three quarters of the 17th centuries, apparently, did not exceed 70 000 people.

As with previous periods, the most abundant material was obtained in pottery. In Otrar was excavated pottery block of the end of 16th century — 80th. Years and several ceramic workshops of the same time in different urban areas. Along with the large pottery workshops, fine craftwork was noted, when a small pottery kiln was arranged in the courtyard of the house. Owners of large workshops in Otrar might have one or more students and part-time workers.

In the block of pottery, artisans, apparently, were united in guilds, such as those that are known from surviving guild ordinances of “risola.” Thus, according to anthropologists, the artisans of Khorezm, who belonged to the same profession, called themselves the “ulpa-gar”, which means “partnership in the profession.” The head of the department was the “kalantar,” who was elected on the shop floor assembly. In the Fergana shop foreman called “bobo” and “elder.” The same terms were used in Samarkand. Interestingly, during the excavation of Turkestan in the layer of the XIX century, there were found fragments of hums with the stamp mark, fixed in one case the master’s name Yunus, the other — the name and the title — “kuloli kalon” — senior potter. Apparently, the master Yunus was the head of department of Turkestan, as they were kalantars of Khorezm, “bobo” and “elders” of Fergana.

The traditions and customs of the guild system, recorded risola, worked out for centuries and, no doubt, existed among the potters of late medieval cities of Kazakhstan. Specialization of production also existed. Thus, it may be noted that in comparison with the period of the early and developed Middle Ages a tendency toward specialization of urban master-potters progressed as they got closer to the new time.

Metallurgy and blacksmithing, as before, were common in the city. Artisans made casting of cast iron boilers. Sleeves for wheels were made of cast iron; they had the characteristic shape of the cage with three projections on the perimeter. Sickles were made of iron. Knives and debris were the most numerous categories of products from iron. Set of iron horseshoes indicates that they have been quite varied in size. Not only horses were shod, but mules and donkeys too.

Copper rafts, as before, played a big role in handicraft production of the city.

Jewelers widely used colored stones in their production: carnelian, fire opal, jasper, jade, agate, jet, serpentine, rock crystal. The stones were used for making necklaces, insertions in rings, as well as ornamental material and for signet rings themselves. Fasteners, plaques and other things were also made from colored stones. As evidenced by items found during the excavations, jewelry craft was characterized by a high level of development. Masters had known and used a variety of techniques: forging, casting, stamping, engraving, invoice filigree, gilding, silver-notch. They knew a method of making silver and bronze wire, cutting and grinding, drilling colored stone. Dishes and jewelry (necklaces, pendants) were manufactured from glass.

Processing of bones was a traditional craft in the Kazakh city. Horns and long bones of wild and domestic animals were used as ornamental material.

A few products made from such widespread crafts like weaving, carpet weaving, and production of leather goods survived. But, according to findings of spindles, the prints on the fabric of sufa, pieces of quilts, pieces of burnt coarse cotton cloth, it is the fact the cities had weavers who produced cloth.

Establishment of trade relations in Central Asia and Russia through the Kazakh steppe and Turkestan city was a new development in the transit trade of the second half of the 15th-18th centuries. Trade with Russia is becoming an important factor in the economic development of Kazakhstan cities. Russia exported cloth, satin, mirror, furs, silver to Kazakhstan and Central Asia. Caravans walked through the Kazakh city — Suzak, Karachuk, Turkestan. Not accidentally sources call Sygnak as a trading harbor of Desht-i Qipchaq.

Information given in written sources are confirmed by archaeological finds. In Otrar, Turkestan, Sauran were found Chinese celadon porcelain of 16th-17th centuries and Russian copper penny.

Along with international trade there is the traditional trade of Syr Darya cities with the nomadic world and local trade. Cities supplied the neighborhood agricultural and nomadic populations with the necessary goods through the bazaar. Bazaars of cities were covered rows of streets. Dukan-shop usually owned by craftsmen, and often served as a workshop, and a place of commerce.

Dukan presence in Turkestan is confirmed by data from written documents pertaining to Waqf mausoleum of Ahmed Yasawi. In Otrar there were identified retail shops that went into the street.

The size of international trade and commerce between the cities and the countryside, and between the individual cities of Syr Darya can be seen in numismatic material, mainly from the excavations of Otrar and Turkestan. Copper coins, indicating the mints of Yasi and Tashkent are typologically homogeneous complex and form the basis of coin hoards of Turkestan and Otrar.

Small copper coins are perhaps the part of coin production of Turkestan court too. Most of the time, instead of inscriptions, there are different signs knocked out on them that are similar to tamgas, portrayed on a ceramic dish.

In the life of medieval fortifications, agriculture has played an important role. Out of town residents had areas of cultivated land, in which they moved in the summer.

Archaeological excavations confirm the important role of the agricultural in the life of citizens. In particular, the size of home space was growing at this time and this is due to iwans, patios, stores, and space for livestock. These changes also show how the economy of the urban population had changed. Household patios, partially closed by canopies, large storage for grain and agricultural products, special facilities for livestock in late medieval Otrar show the agrarization of the city of that time.

By describing the development of the city and settled culture, it should be noted the continuity of tradition and the culture of an earlier time, and the fact that much of what was created in the late medieval city, became an integral part of the culture of the Kazakh people.